Memory management in Extempore

It’s not really possible to explain Extempore’s memory allocation story without a detour into xtlang types, so we’ll cover some of that as well.

The two languages hosted by the Extempore compiler, xtlang and Scheme, have different approaches to allocating & managing memory. Both languages ultimately share the same memory—the stack and heap associated with the Extempore process—but via different mechanisms.

Broadly speaking, with Scheme code Extempore manages memory for you, while in xtlang you have to do it yourself. This is a common trade-off, and each has its advantages (in performance, programmer productivity, etc.) and disadvantages. So if you’re mostly going to be writing Scheme code (e.g. you’re making music using the built-in instruments) then you probably don’t need to read this (although understanding how things work under the hood is still sometimes helpful). To work effectively in xtlang, though, you’ll need to now a bit more about memory in Extempore.

Automatic garbage collection in Scheme

Scheme objects (lists, closures, numbers, etc.) are automatically garbage collected by the Extempore run-time garbage collector (GC). This means that when new objects are created, memory is automatically allocated to store those objects, and as objects are destroyed or go out of scope (that is, there are no longer any references to them) the memory is automatically freed up for re-use.

Let’s do the most basic memory allocation imaginable: just binding a numerical value to a symbol.

(define a 5)

(println 'a '= a) ;; prints a = 5

The fact that we can use the symbol a and have it evaluate to 5 (as it

should) means that the value (5) must be stored in memory somewhere. It

doesn’t matter where in memory (what the address is), because we can always

refer to the value using the symbol a. But it’s good to remember that the

define form is allocating some memory, storing the value 5 in that memory,

and binding a reference to the value in the symbol a.

We can redefine the symbol a to be some other Scheme object, say, a list.

(define a '(1 2 3))

(println 'a '= a) ;; prints a = (1 2 3)

The three-element list (1 2 3) takes up more memory than the number 5. So

define can’t just write the new value of a over the top of the old one. What

it does (and in fact what re-defining things always does) is allocate some new

memory to store the new value into, and change the variable a to point to that

new value.

But what happens to the old value of 5 in memory? Well, it sits there

untouched, at least for a while. But we can’t reach it—the only ‘handle’ we

had to refer to it with was the symbol a, and that’s now bound to some other

value instead. The value 5 in memory is ‘unreachable’. So there’s no point

having it sitting around, taking up space.

That’s where the garbage collector comes in. Every now and then the garbage collector checks all the Scheme objects in the world, determines which of them are no longer reachable, and then frees up that memory to be used for other things. While I don’t recommend this harsh utilitarian approach to dealing with relatives who are down on their luck, it is good idea in a computer program. Memory is a finite resource, and the more efficiently we can get rid of memory that’s not being used the better.

Basically, having a GC means that when you’re writing Scheme code, you don’t have to worry about memory. The GC takes care of all the allocation/deallocation bookkeeping for you. The cost is that this bookkeeping requires CPU cycles—cycles which you could be using to do other cool things. Also, every now and then the GC has to briefly ‘stop the world’ (freeze the execution of all Scheme code) to do its job. This takes time, and introduces an element of uncertainty (non-determinism) to the execution of your code—you never know exactly when the GC is going to freeze things to do it’s job, and there’s a risk that it’ll happen at a really inconvenient time as far as your program is concerned (Murphy’s law and all that). This is particularly problematic in domains where timing is critical, such as real-time audio and video.

Manual memory management in xtlang

Hang on a sec—isn’t working with real-time audio and video xtlang (and therefore Extempore’s) raison d’etre? Well, yes is is—the sluggishness (and non-determinism) of Impromptu’s Scheme interpreter was the spark which ignited the development of xtlang (as mentioned in philosophy). Again, this isn’t a knock on Scheme in general as slow—there are some very sprightly Scheme compilers, but Impromptu’s one was slow. The non-determinism was even more of a problem, because the last thing you want when you’re generating audio or video is a ‘stop the world’ GC pause, which will lead to clicks and pops in audio or dropped frames in video. Real-time systems and garbage collection are uneasy bedfellows.

So, xtlang requires manual memory management. In general, this means that when you want some memory you ask the compiler for it, it’s yours for a time and you can do whatever you want with it, and then you know when it’s going to be ‘given back’. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you have it forever (in fact in many cases the memory is quite short-lived), but it does mean that there are no surprises—you specify exactly how much memory you’ll get and you know it’s going to hang around for. This determinism an important benefit of manual memory management in xtlang—especially in a real-time systems context.

Zooming out for a second, a running program has access to and uses two main regions of memory: the stack and the heap. There’s lots of material on the web about the differences between these two a (here’s an explanation at stackoverflow), but I’ll give a quick summary here.

- The stack is for dealing with function arguments and local variables. Each function call ‘pushes’ some new data onto the stack, and when the function returns it ‘pops’ off any local variables and leaves its return value. The stack is therefore generally changing pretty quickly.

- The heap, on the other hand, is for longer-lived data. Buffers of audio, video, or any data which you want to have around for a while: these are the sort of things you’ll generally want to store on the heap.

I should also point out that the stack and heap aren’t actually different types of memory in the computer—they’re just different areas in the computer’s RAM. The difference is in the way the program uses the different regions. Each running process has its own stack(s) and heap, and they are just regions of memory given to the process by the OS.

So, that’s the stack and the heap, but there’s actually one other type of memory in Extempore: zone memory. A zone is a region of memory which can be easily deallocated all at once. So, if you have some data that you need to hang around longer than a function call (so a stack allocation is no good), but want to be able to conveniently deallocate all at once, then use a zone. There can be multiple zones in existence at once, and they don’t interfere (or have anything to do with) each other.

The three flavours of memory in Extempore

So, in accordance with the three different memory ‘types’ (stack, heap, and

zone) there are three memory allocation functions in xtlang: salloc, halloc

and zalloc. They all return a pointer to some allocated memory, but they

differ in where that memory is allocated from, and there are no prizes in

guessing which function is paired with which type of memory :)

Also, alloc in xtlang is an alias for zalloc. So if you ever see an alloc

in xtlang code it’s grabbing memory from a zone.

Stack allocation with salloc

As I mentioned above, the stack is associated with function calls, their

arguments and local variables. Because xtlang uses (in general)

closures rather

than just plain functions, stack allocation and salloc in xtlang is used in

the body of a closure. Remember that closures are just functions with their

enclosing scope: think of a function which has packaged up any variables it

references and carries them around in its saddlebags.

Well, that’s as clear as mud. Let’s have an example.

(bind-func simple_stack_alloc

(lambda ()

(let ((a 2)

(b 3.5))

(printf "a x b = %f\n"

(* (i64tod a) b)))))

(simple_stack_alloc) ;; prints "a x b = 7.000000"

Even though there was no explicit call to salloc, the local variables which

are bound in the let (in this case the integer a and the float b) are

allocated on the stack. This is always where the memory for let-bound float

and int literals is allocated from in xtlang. String literals are bound globally

(more on this shortly), but that’s the exception to the rule—everything else

which is bound in a let inside an xtlang lambda will be stack allocated,

unless you explicitly request otherwise with halloc or zalloc.

String literals

are the exception to the “all literals are on the stack” rule. String literals

are actually stored as i8* on the heap (as though they were halloced). If

you capture a pointer to one of these strings (e.g. with pref-ptr), then you

can pass it around and dereference it from anywhere.

This ‘implicit stack allocation’ works for int and float literals, but how about

aggregate and other higher-order types? In those cases, we call salloc

explicitly.

(bind-func double_tuple

(lambda (a:i64)

(let ((tup:<i64,i64>* (salloc)))

(printf "input: %lld, " a)

(tfill! tup a (* 2 a))

(printf "output: <%lld,%lld>\n"

(tref tup 0)

(tref tup 1))

tup)))

(double_tuple 3) ;; prints "input: 3, output: <3,6>"

This double_tuple closure takes an i64 argument, and creates a 2-tuple which

contains the input value and also its double. Think of it as creating

input-output pairs for the function f(x) = 2x.

Notice how the tuple pointer tup:<i64,i64>* was let-bound to the return

value of the call to salloc. Initially, the memory was uninitialised (see

here for more

background about pointers), then two i64 values were filled into it with

tfill!. This is basically all the closure does, apart from the printf calls

which are just reading and printing out what’s going on.

The printout confirms that the doubling is working correctly: 6 is indeed what

you get when you double 3, so the output value of <3,6> is spot on. The

pointer (and memory) returned by (salloc) is obviously working fine. And this

pointer is also the return value of the closure (so double_tuple has type

signature [<i64,i64>*,i64]*).

What happens if we try and dereference this returned pointer?

(bind-func double_tuple_test

(lambda ()

(let ((tup (double_tuple 6)))

(printf "tup* = <%lld,%lld>\n"

(tref tup 0)

(tref tup 1)))))

(double_tuple_test)

;; prints:

;; input: 6, output: <6,12>

;; tup* = <6,12>

Well, that seems to work OK. What about if we call double_tuple again in the

body of the let, ignoring its return value?

(bind-func double_tuple_test2

(lambda ()

(let ((tup (double_tuple 6)))

(double_tuple 2)

(printf "tup* = <%lld,%lld>\n"

(tref tup 0)

(tref tup 1)))))

(double_tuple_test2)

;; prints:

;; input: 6, output: <6,12> (in the 1st call to double_tuple)

;; input: 2, output: <2,4> (in the 2nd call to double_tuple)

;; tup* = <2,4>

This isn’t right: tup* should still be the original tuple <6,12>, because

we’ve bound it the let. But somewhere in the process of calling double_tuple

again (with a different argument: 2), the values in our original tuple (which

we have a pointer to in tup) have been overwritten.

Finally, consider this example:

(bind-func double_tuple_test3

(lambda ()

(let ((tup (double_tuple 6))

(test_closure

(lambda ()

(printf "tup* = <%lld,%lld>\n"

(tref tup 0)

(tref tup 1)))))

(test_closure))))

(double_tuple_test3)

;; prints:

;; input: 6, output: <6,12>

;; tup* = <0,4508736416>

Wow. That’s not just wrong, that’s super wrong. What’s going on is that the

call to salloc inside the closure double_tuple doesn’t keep the memory after

the closure returns, because at this point all the local variables get popped

off the stack. Subsequent calls to any closure will push new arguments and

local variables onto the stack and overwrite the memory that tup points to.

That’s what deallocating memory means: it doesn’t mean that the memory gets set to zero, or that new values will be written in straight away, but it means that the memory might be overwritten at any stage. Which, from a programming perspective, is just as bad as having new data written into it, because if you can’t trust that your pointer still points to the value(s) you think it does then it’s pretty useless.

So, what we need in this case is to allocate some memory which will still hang

around after the closure returns. salloc isn’t up to the task, but zalloc

is.

Zone allocation with zalloc

Zone allocation is kindof like stack allocation, except with user control over when the memory is freed (as opposed it happening at the end of function execution, as with memory on the stack). Essentially this means that we can push and pop zones off of a stack of memory zones of user-defined size.

A memory zone can be created using the special memzone form. memzone takes

as a first argument a zone size in bytes, and then an arbitrary number of other

forms (s-expressions) which make up the body of the memzone. The extent of

the zone is defined by memzone’s s-expression. Anything within the body of the

memzone s-expression is in scope.

Say we want to fill a memory region with i64 values which just count from 0

up to the length of the region (region_length). We’ll need to allocate the

memory for this region, and get a pointer to the start of the region. We can do

this using zalloc inside a memzone.

(bind-func fill_buffer_memzone

(lambda ()

(memzone 100000 ;; size of memzone (in bytes)

(let ((region_length 1000)

(int_buf:i64* (zalloc region_length))

(i:i64 0))

(dotimes (i region_length)

(pset! int_buf i i))

(printf "int_buf[366] = %lld\n"

(pref int_buf 366))))))

(fill_buffer_memzone) ;; prints "int_buf[366] = 366"

The code works as it should: as confirmed by the print statement. Notice how the

call to zalloc took an argument (region_length). This tells zalloc how

much memory to allocate from the zone. If we hadn’t passed this argument (and it

is optional), the default length is 1, to allocate enough memory for one

i64. All of the alloc functions (salloc, halloc and zalloc) can take

this optional size argument, and they all default to 1 if no argument is

passed.

Let’s try another version of this code fill_buffer_memzone2, but with a much

longer buffer of i64 values.

(bind-func fill_buffer_memzone2

(lambda ()

(memzone 100000 ;; size of memzone (in bytes)

(let ((region_length 1000000)

(int_buf:i64* (zalloc region_length))

(i:i64 0))

(dotimes (i region_length)

(pset! int_buf i i))

(printf "int_buf[366] = %lld\n"

(pref int_buf 366))))))

(fill_buffer_memzone2) ;; prints "int_buf[366] = 366"

This time, with a region length of one million, the code still works (at least, the 367th element is still correct).

memzone calls can also be nested inside one another. When a new zone is

created (pushed) any calls to zalloc will be allocated from the new zone

(which is the top zone of the “zone stack”). When the extent of the zone

(i.e. the closing ) of the memzone form) is reached it is popped and its

memory is reclaimed. The new current zone is then the next top zone.

By default each process has an initial top zone with 1M of memory. If no

user defined zones are created (i.e. no uses of memzone) then any and all

calls to zalloc will slowly (or quickly) use up this 1M of memory. However, if

the memory from a zone is exhausted, then Extempore will automatically allocate

another chunk of memory (the same length as the original length of that zone).

This might cause slight a slight performance hit in some circumstances, hence

the ability to set the zone size manually if necessary.

In general this is the zone story. But to complicate things slightly there are two special zones.

-

The audio zone: there is a zone allocated for each audio frame processed, be that sample by sample, or buffer by buffer. The zones extent is for the duration of the audio frame (i.e. is deallocated at the end of the frame).

-

Closure zones: all ‘top level’ closures (any closure created using

bind-func) has an associated zone created at compile time (not at run-time, although this distinction is quite blurry in Extempore). Thebind-funczone default size is 8KB, however,bind-funchas an optional argument to specify any arbitrarybind-funczone size.

To allocate memory from a closure’s zone, we need a let outside the lambda.

Anything zalloc‘ed from there will come from the closure’s zone. Anything

zalloc‘ed from inside the closure will come from whatever the top zone is at

the time—usually the default zone (unless you’re in an enclosing memzone).

As an example, note the ‘zone size’ argument to bind-func

(bind-func fill_buffer_closure_zone2 10000 ;; zone size: 10KB

(let ((region_length 1000)

(int_buf:i64* (zalloc region_length))

(i:i64 0))

(lambda ()

(dotimes (i region_length)

(pset! int_buf i i))

(printf "int_buf[366] = %lld\n"

(pref int_buf 366)))))

(fill_buffer_closure_zone2) ;; prints "int_buf[366] = 366"

This type of thing is very useful for holding data closed over by the top level

closure. For example, an audio delay closure might specify a large bind-func

zone size and then allocate an audio buffer to be closed over. The example file

examples/core/audio-dsp.xtm has lots of examples of this.

The bind-func zone will live for the extent of the top level closure, and will

be refreshed if the closure is rebuilt (i.e. the old zone will be destroyed and

a new zone allocated).

Heap allocation with halloc

Finally, we meet halloc, the Extempore function for allocating memory from the

heap. The heap is for long-lived memory, such as data that you want to keep

hanging around for the life of the program.

You can use halloc anywhere you would use salloc or zalloc and it will

give you a pointer to some memory on the heap. So, let’s revisit the

double_tuple_test3 example from earlier, which didn’t work because the memory

for tup on the stack went out of scope when the closure returned. If we

replace the salloc with a halloc:

(bind-func double_tuple_halloc

(lambda (a:i64)

(let ((tup:<i64,i64>* (halloc))) ;; halloc instead of salloc

(tfill! tup a (* 2 a))

tup)))

(bind-func double_tuple_halloc_test

(lambda ()

(let ((tup (double_tuple_halloc 4))

(test_closure

(lambda ()

(printf "tup* = <%lld,%lld>\n"

(tref tup 0)

(tref tup 1)))))

(test_closure))))

(double_tuple_halloc_test) ;; prints "tup* = <4,8>"

Now, the returned tuple pointer tup is a heap pointer, so we can refer to it

from anywhere without any issues. In fact, the only way to deallocate memory

which has been halloc‘ed and free it up for re-use is to use the xtlang

function free (which is the same as calling free in C).

In practice, a lot of the times where you want long-lived memory you’ll want it

to be associated with a closure anyway, so the closure’s zone is a better option

than the heap for memory allocation, as in the fill_buffer_closure_zone2

example above. This has the added advantage that if you re-compile the closure,

because you’ve changed the functionality or whatever, all the memory in the zone

is freed and re-bound, which is often what you want.

Where you may want to use halloc to allocate memory on the heap, is in

binding global data structures which you want to have accessible from anywhere

in your xtlang code. Binding global xtlang variables is the job of bind-val.

Choosing the right memory for the job

Each different alloc function is good for different things, and the general idea

to keep in mind is that you want your memory to hang around for as long as you

need it to—and no longer. Sometimes you only need data in the body of a

closure—then salloc is the way to go. Other times you want it to be around

for as long as the closure remains unchanged, then zalloc is the right choice.

Also, if you’re going to be alloc’ing a whole lot of objects for a specific

algorithmic task and want to be able to conveniently let go of them all when

you’re done, then creating a new zone with memzone and using zalloc is a

good way to go. Finally, if you know that a particular buffer of data is going

to hang around for the life of the program, then use halloc.

It’s worth acknowledging that memory management in xtlang is a ‘training wheels

off’ scenario. It’s a joy to have the low level control and performance of

direct memory access, but there are also opportunities to really mess things up

in a way that’s trickier to do in higher-level languages. Remember that memory

is a finite resource. Don’t try and allocate a memory region of 1015

8-byte i64:

(bind-func fill_massive_buffer

(lambda ()

(let ((region_length 1000000000000000)

(int_buf:i64* (zalloc region_length))

(i:i64 0))

(dotimes (i region_length)

(pset! int_buf i i))

(printf "int_buf[366] = %lld\n"

(pref int_buf 366)))))

(fill_massive_buffer)

When I call (fill_massive_buffer) on my computer (with 8GB of RAM), disaster

strikes.

Compiled: fill_massive_buffer >>> [i32]*

Process extempore segmentation fault: 11

If you’re not used to working directly with memory, you’ll almost certainly crash (segfault) Extempore when you start out. In fact, be prepared to crash things a lot at first. Don’t be discouraged: once you get your head around the three-fold memory model and where each allocation function is getting its memory from, it’s much easier to write clean and performant code in xtlang. And from there, the performance and control of working with ‘bare metal’ types opens up lots of cool possibilities.

Pointers

xtlang’s pointer types may cause some confusion for those who aren’t used to (explicitly) working with reference types. That’s nothing to be ashamed of—the whole pass by value / pass by reference thing can take a bit to get your head around.

So what does it mean to say that xtlang supports pointer types? Simply put, this means that we can use variables in our program to store not just values, but the addresses of values in memory. A few examples might help to clarify things.

The let form in xtlang (as in Scheme) is a way of binding or assigning

variables: giving a name to a particular value. If we want to keep track of the

number of cats you have, then we can create a variable num_cats

(bind-func print_num_cats

(lambda ()

(let ((num_cats:i64 4))

;; the i64 printf format specifier is %lld

(printf "You have %lld cats!\n" num_cats))))

(print_num_cats) ;; prints "You have 4 cats!"

What’s happening here is that the let assigns the value 4 to the variable

num_cats, so that whenever the program sees the variable num_cats it’ll look

in the num_cats ‘place’ in memory and use whatever value is stored there. The

computer’s memory is laid out like a row of little boxes, and each box has an

address (the location of the box) and also a value (what’s in the box).

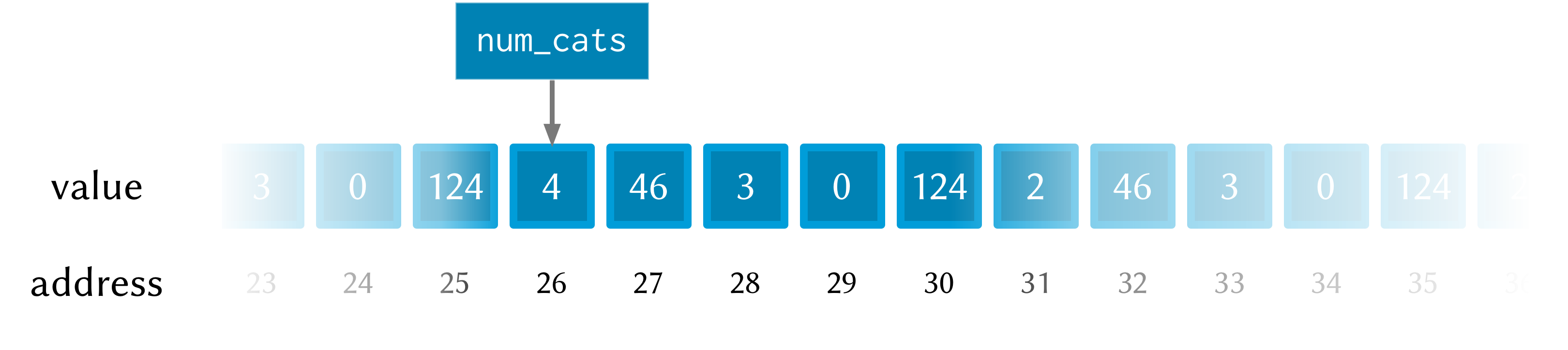

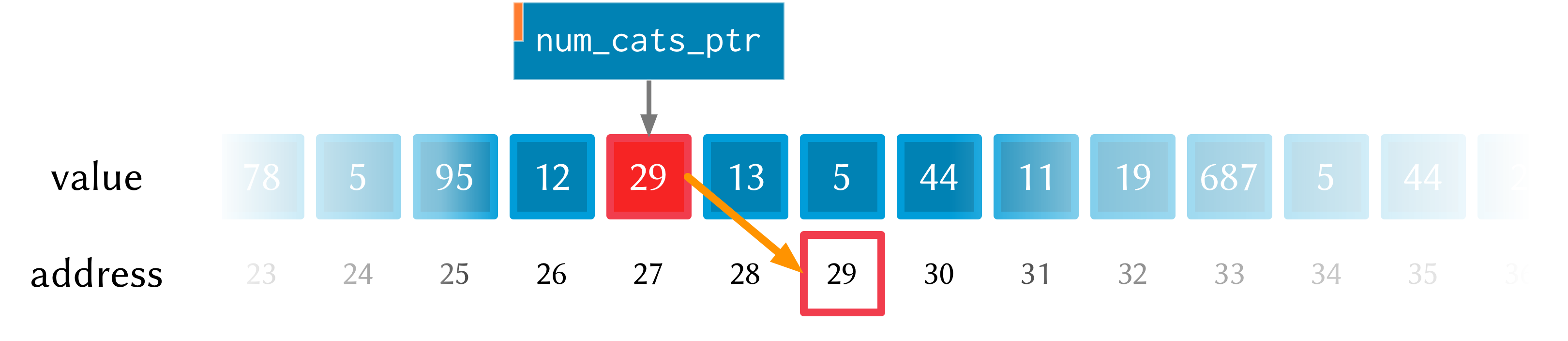

In this image the computer’s memory is represented by the blue boxes. Each box has an address (the number below the box), an in this picture you can see that this is only a subset of the total number of memory boxes (in a modern computer there are millions of memory boxes).

The variable num_cats keeps track of the value that we’re interested in. In

this case the address of that value is ‘memory location 26’, but it could easily

be any other location (and indeed will almost certainly be different if the

closure print_num_cats is called again).

Once a variable exists, we can change its value with set!:

(bind-func print_num_cats2

(lambda ()

(let ((num_cats:i64 4))

(printf "You have %lld cats... " num_cats)

(set! num_cats 13)

(printf "and now you have %lld cats!\n" num_cats))))

(print_num_cats2)

;; prints "You have 4 cats... and now you have 13 cats!"

The set! function changes the value of num_cats: it sets a new value into

the memory location that num_cats refers to. In print_num_cats2 the value of

num_cats starts out as 4, so the first printf call prints “You have 4

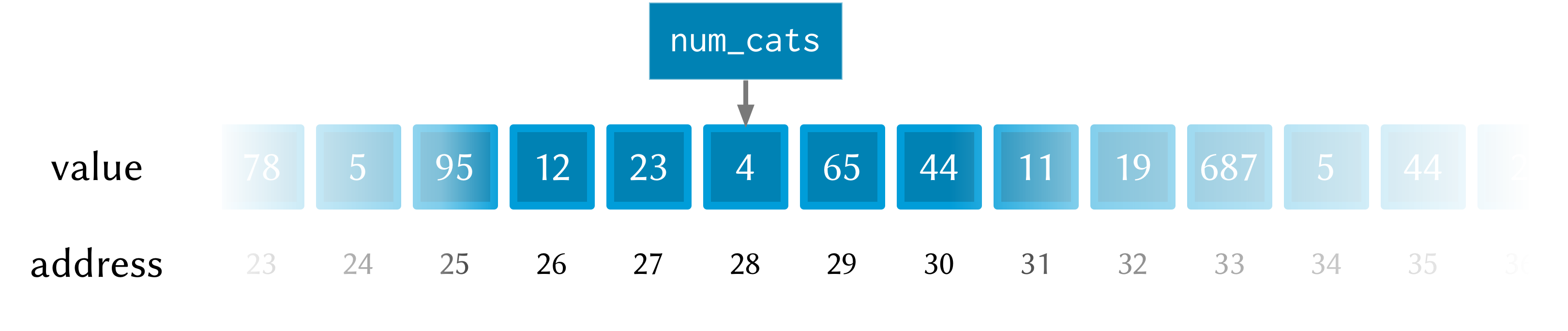

cats…”. The memory at this point might look like this:

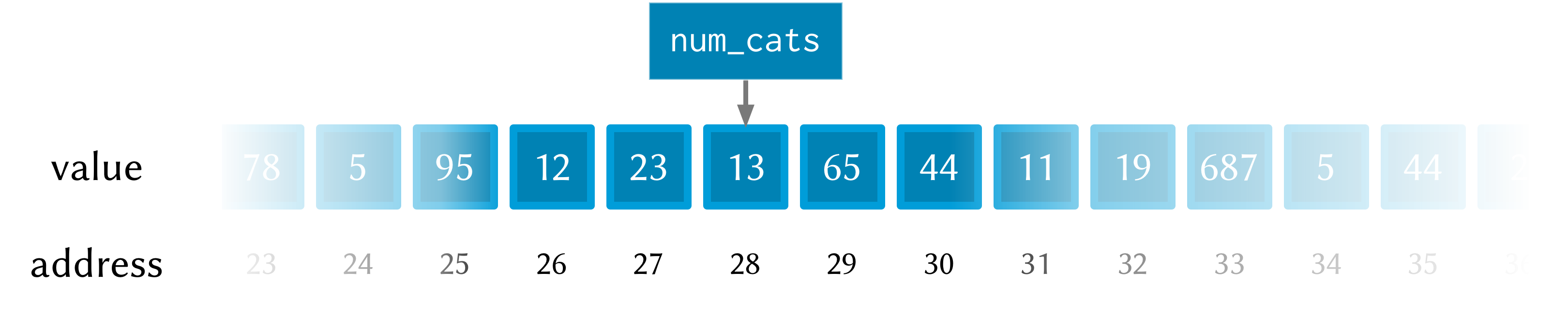

But then a new value (13) is set into num_cats with the call to set!, so

the second call to printf prints “and now you have 13 cats!”. After the call

to set!, this is what the memory looks like:

Notice how this time the memory address for num_cats is different to what it

was the previous time (28 rather than 26). This is because the let rebinds all

its variable-value pairs each time it is entered, and then forgets them when it

is exited (that is, when the paren matching the opening paren is reached).

Pointers: storing memory addresses as values

What we’ve done so far is store the value (how many cats we have) into the

variable num_cats. The value has an address in memory, but as a programmer we

don’t necessarily know what that address is, just that we can refer to the value

using the name num_cats. It’s important to note that the compiler knows what

the address is—in fact as far as the compiler is concerned every variable is

just an address. But the compiler allows us to give these variables names, which

makes the code much easier to write and understand.

Pointer types in xtlang are indicated with an asterisk (*), for example the

type i64* represents a pointer to a 64-bit integer (sometimes called an

i64-pointer). With pointers, we actually assign the address itself in a

variable. That’s the reason it’s called a pointer: because it points to (is a

reference to) the value.

Let’s update our code for printing the number of cats to use a pointer to the

value, rather than the value itself. Notice how the type of num_cats_ptr is

i64* (a pointer to an i64) rather than just an i64 like it was before.

(bind-func print_num_cats3

(lambda ()

(let ((num_cats_ptr:i64* (zalloc)))

(printf "You have %lld cats!\n" num_cats_ptr))))

(print_num_cats3) ;; prints "You have 4555984976 cats!"

There are a couple of other changes to the code. Firstly, we no longer bind the

value straight away (as we were doing with (num_cats:i64 4)), but instead we

make a call to zalloc. This is the way to get pointers in xtlang: through a

call to an ‘alloc’ function. zalloc is a function which ‘allocates’ and

returns the address (i.e. a pointer) of some memory which can be used to store

the value in. This address is the assigned to the variable num_cats_ptr, just

like the number 4 was assigned to num_cats in the earlier examples. The

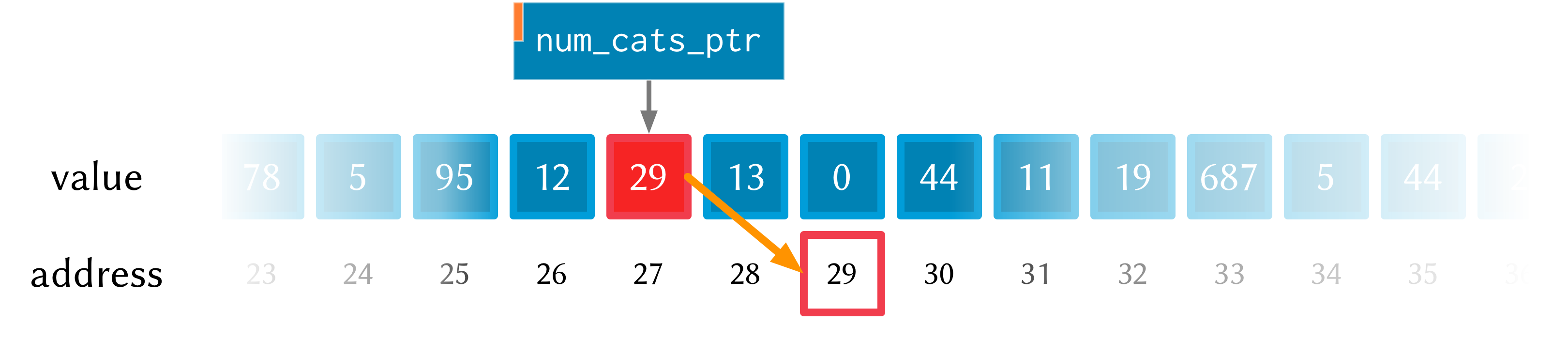

orange bar on the variable name indicates that it’s a pointer.

So why does print_num_cats3 print such a weird (on my machine: 4555984976

cats!) answer? Well, it’s because we’re trying to print it as an i64 value

(using %lld in the printf format string), but it’s not an i64 value—it’s

the address of a memory location where an i64 value is located. On a 64-bit

system (such as the laptop I’m writing this blog post on) the pointers are

actually 64-bit integers, because an integer is a pretty sensible way to store

an address.

Incidentally, this is one of the key benefits (and driving forces behind) the switch from 32 to 64 bit architectures—the need for more memory addresses. If a pointer is a 32 bit integer, then you can only ‘address’ about 4.3 billion (232) different memory locations. This might seem like a lot, but as more and more computers came with more than 4.3Gb of RAM installed, so the need for 64-bit pointers became more pressing. There are workarounds, but having a larger addressable space is a key benefit of 64-bit architectures. And it helps to remember that pointers are just integers, but they’re not like the int types that we use to store and manipulate data.

In print_num_cats3 we don’t set any value into that location, we only deal

with the address. In fact, the memory this address points to is referred to as

uninitialised, which is a name for memory that has been allocated but hasn’t

had any values set into it. In Extempore, uninitialised memory will be ‘zeroed

out’, meaning all of the bits will be set to 0. So for an i64 this will be

the integer value 0.

After the call to zalloc, the memory therefore will look like this (the value

is now shown in a different coloured box, to indicate it’s an i64* pointer

type and not an i64 value type)

This is cool, we can see that the value in memory location 27 is actually the

address 29, and the value of 29 is 0 because we haven’t initialised it yet.

So, remember how in print_num_cats2 we used set! to set a value into the

variable num_cats? Well, we can do a similar thing with the pointer

num_cats_ptr using the function pset!. pset! takes three arguments: a

pointer, an index (which is zero in this next example, but I’ll get to what the

index means in the next section) and a value. The value must be of the right

type: e.g. if the pointer is a pointer to a double (a double*) then the value

must be a double.

(bind-func print_num_cats4

(lambda ()

(let ((num_cats_ptr:i64* (zalloc)))

(pset! num_cats_ptr 0 5)

(printf "You have %lld cats!\n" (pref num_cats_ptr 0)))))

(print_num_cats4) ;; prints "You have 5 cats!"

Great—the function now prints the right number of cats (in this case 5), so

things are working properly again. After the pset! call, the memory will look

like this (the only difference from last time is that the value 5 is stored in

address 29, just as it should be).

Notice also that in print_num_cats4 we don’t pass num_cats_ptr directly to

printf, we do it through a call to pref. Whereas pset! is for writing

values into memory locations, pref is for reading them out. Like pset!, pref

takes a pointer as the first argument and an offset for the second argument. In

this way, we can read and write i64 values to the memory location without

actually having a variable of type i64 (which we did with num_cats in the

print_num_cats and print_num_cats2). All this is possible because we have a

pointer variable (num_cats_ptr) which gives us a place to load and store the

data.

Buffers and pointer arithmetic

In all the examples so far, we’ve only used a pointer to a single value. This has worked fine, but you might have been wondering why we bothered, because assigning values directly to variables (as we did in the first couple of examples) seemed to work just fine.

One thing that pointers and alloc’ing allows us to do is work with whole regions in memory, in which we can store lots of values. Say we want to be able to determine the mean (average) of 3 numbers. One way to do this is to store each of the different numbers with its own name.

(bind-func mean1

(lambda ()

(let ((num1:double 4.5)

(num2:double 3.3)

(num3:double 7.9))

(/ (+ num1 num2 num3)

3.0))))

;; call the function

(mean1) ;; returns 5.233333

The let form binds the (double) values 4.5, 3.3 and 7.9 to the names

num1, num2 and num3. Then, all three values are added together (with +)

and then divided by 3.0 (with /). Now, this code does give the right answer,

but it’s easy to see how things would get out of hand if we wanted to find the

mean of 5, 20 or one million values. What we really want is a way to give one

name to all the values we’re interested in, rather than having to refer to all

the values by name individually. And to do that, we can use a pointer.

(bind-func mean2

(lambda ()

(let ((num_ptr:double* (zalloc 3)))

;; set the values into memory

(pset! num_ptr 0 4.5)

(pset! num_ptr 1 3.3)

(pset! num_ptr 2 7.9)

;; read the values back out, add them

;; together, and then divide by 3

(/ (+ (pref num_ptr 0)

(pref num_ptr 1)

(pref num_ptr 2))

3.0))))

(mean2) ;; returns 5.233333

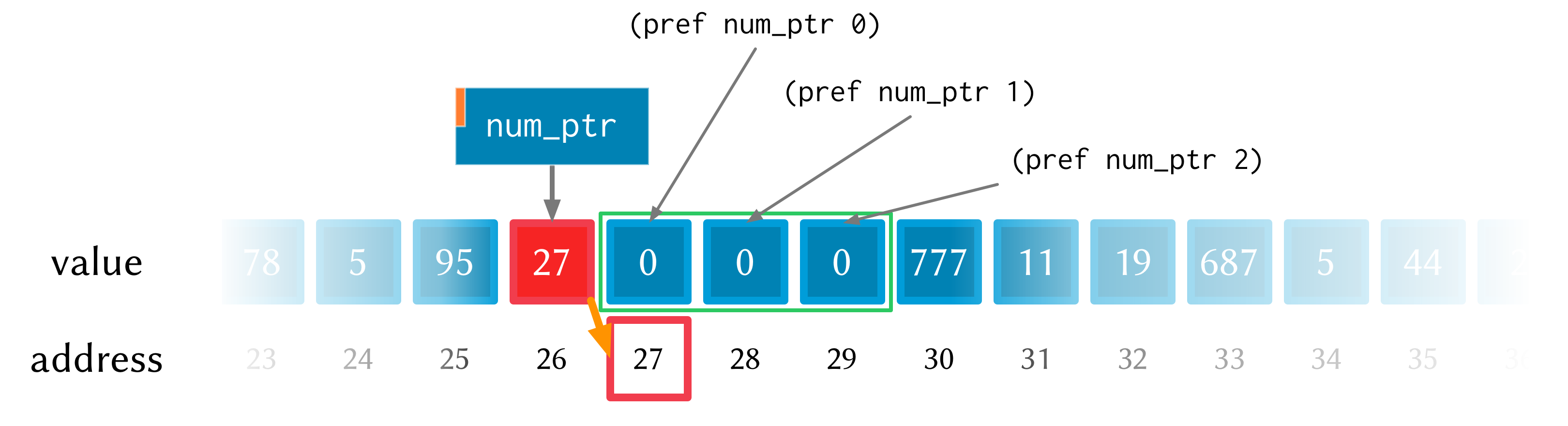

In mean2, we pass an integer argument (in this case 3) to zalloc.

zalloc then allocates enough memory to fit 3 double values. The

pointer that gets returned is still only a pointer to the first of these

memory slots. And this is where the second ‘offset’ argument to pref

and pset! come in.

See how the repeated calls to pset! and pref above have different offset

values? Well, that’s because the offset argument allows you to get and set

values ‘further into’ the memory returned by (zalloc 3). This isn’t anything

magical, they just add the offset to the memory address.

There is a helpful function called pfill! for filling multiple values into

memory (multiple calls to pset!) as we did in the above example. Rewriting

mean2 to use pfill!:

(bind-func mean3

(lambda ()

(let ((num_ptr:double* (zalloc 3)))

;; set the values into memory

(pfill! num_ptr 4.5 3.3 7.9)

;; read the values back out, add them

;; together, and then divide by 3

(/ (+ (pref num_ptr 0)

(pref num_ptr 1)

(pref num_ptr 2))

3.0))))

(mean3) ;; returns 5.233333

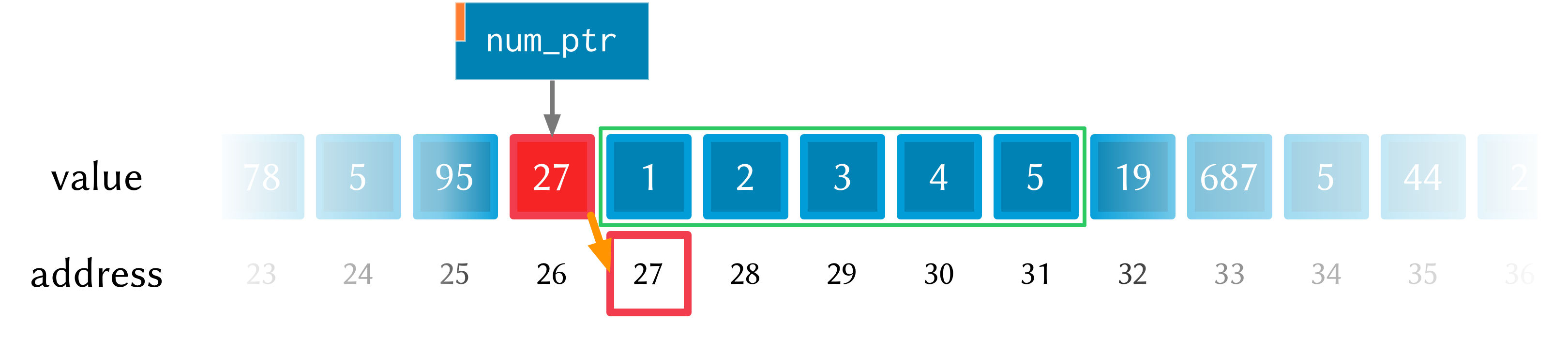

Finally, one more useful way to fill values into a chunk of memory is using a

dotimes loop. To do this, we need to bind a helper value i to use as an

index for the loop. This function allocates enough memory for 5 i64 values,

and just fills it with ascending numbers:

(bind-func ptr_loop

(lambda ()

(let ((num_ptr:i64* (zalloc 5))

(i:i64 0))

;; loop from i = 0 to i = 4

(dotimes (i 5)

(pset! num_ptr i i))

(pref num_ptr 3))))

(ptr_loop) ;; returns 3

After the dotimes the memory will look like this:

There’s one more useful function for working with pointers: pref-ptr. Where

(pref num_ptr 3) returns the value of the 4th element of the chunk of memory

pointed to by num_ptr, (pref-ptr num_ptr 3) returns the address of that

value (a pointer to that value). So, in the example above, num_ptr points to

memory address 27, so (pref num_ptr 2) would point to memory address 29.

(pref (pref-ptr num_ptr n) 0) is the same as (pref (pref-ptr num_ptr 0) n)

for any integer n.

Pointers to higher-order types

The xtlang type system <types> has both primitive types (floats and ints) and higher-order types like tuples, arrays and closures. Higher-order in this instance just means that they are made up of other types, although these component types may be themselves higher-order types.

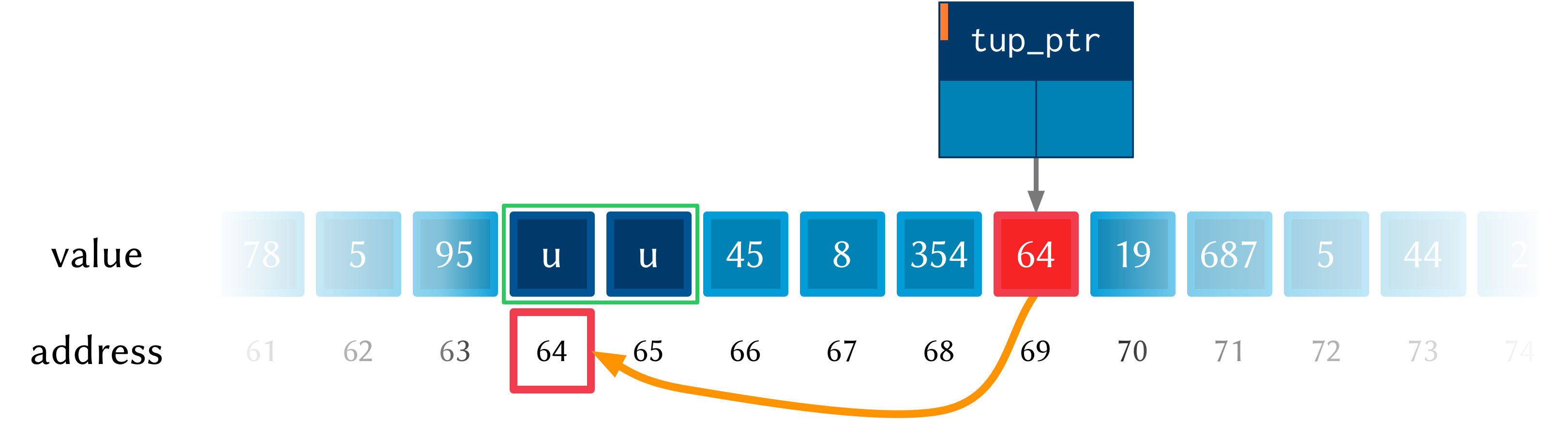

As an example of an aggregate type, consider a 2 element tuple. Tuples are

(fixed-length) n-element structures, and are declared with angle brackes (<>).

So a tuple with an i64 as the first element and a double as the second element

would have the type signature <i64,double>. Getting and setting tuple elements

is done with tref and tset! respectively, which both work exactly like

pref=/=pset! except the first argument has to be a pointer to a tuple.

(bind-func print_tuples

(lambda ()

;; step 1: allocate memory for 2 tuples

(let ((tup_ptr:<i64,double>* (zalloc 2)))

;; step 2: initialise tuples

(tset! (pref-ptr tup_ptr 0) 0 2) ; tuple 1, element 1

(tset! (pref-ptr tup_ptr 0) 1 2.0) ; tuple 1, element 2

(tset! (pref-ptr tup_ptr 1) 0 6) ; tuple 2, element 1

(tset! (pref-ptr tup_ptr 1) 1 6.0) ; tuple 2, element 2

;; step 3: read & print tuple values

(printf "tup_ptr[0] = <%lld,%f>\n"

(tref (pref-ptr tup_ptr 0) 0) ; tuple 1, element 1

(tref (pref-ptr tup_ptr 0) 1)) ; tuple 1, element 2

(printf "tup_ptr[1] = <%lld,%f>\n"

(tref (pref-ptr tup_ptr 1) 0) ; tuple 2, element 1

(tref (pref-ptr tup_ptr 1) 1))))); tuple 2, element 2

(print_tuples) ;; prints

;; tup_ptr[0] = <2,2.000000>

;; tup_ptr[1] = <6,6.000000>

This print_tuples example works in 3 basic steps:

- Allocate memory for two (uninitialised)

<i64,double>tuples, bind pointer to this memory totup_ptr. - Initialise tuples with values (in this case

2and2.0for the first tuple and6and6.0for the second one). Notice the nestedtset!andpref-ptrcalls:pref-ptrreturns a pointer to the tuple at offset 0 (for the first) and 1 (for the second). This pointer is then passed as the first argument totset!, which fills it with a value at the appropriate element. - Read (& print) values back out of the tuples. These should be the values we just set in step 2—and they are.

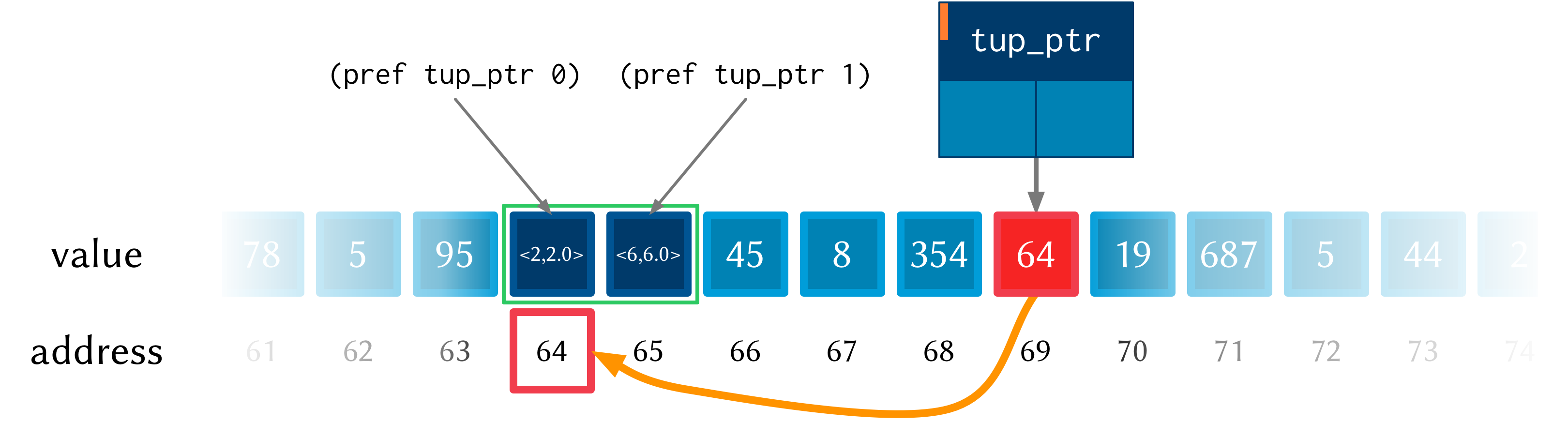

Let’s have a look at what the memory will look like during the execution of

print_tuples. After the call to (zalloc) (step 1), we have a pointer to a

chunk of memory, but the tuples in this memory are uninitialised (indicated by

u).

After using pref and tset! in step 2, the values get set into the tuples.

Step 3 simply reads these values back out—it doesn’t change the memory.

There are a couple of other things worth discussing about this example.

- We used

pref_ptrrather thanprefin both step 2 and step 3. That’s becausetset!andtrefneed a pointer to a tuple as their first argument, and if we had used regularprefwe would have got the tuple itself. This means that we could have just usedtup_ptrdirectly instead of(pref-ptr tup_ptr 0)in a couple of places, because these two pointers will always be equal (have a think about why this is true). - There are a few bits of repeated code, for example

(pref-ptr tup_ptr 1)gets called 4 times. We could have stored this pointer in a temporary variable to prevent these multiple dereferences, how could we have done that (hint: create the new ‘tmp’ pointer in thelet—make sure it’s of the right type).

There’s one final thing worth saying about pointers in xtlang. Why do pointers even have types? Isn’t the address the same whether it’s an int, a float, a tuple, or some complex custom type stored at that memory address? The reason is to do with something all this talk of memory locations as ‘boxes’ has glossed over: that different types require different amounts of memory to store.

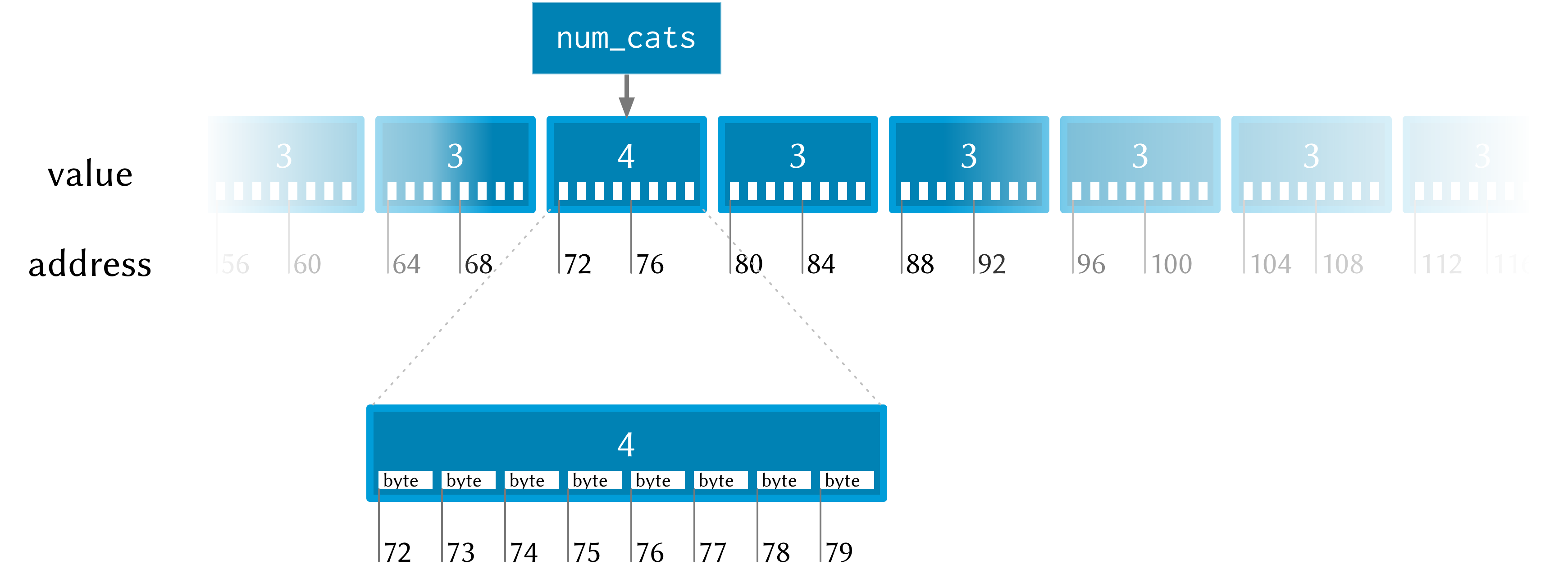

A more accurate (though still simplified) picture of the computer’s memory is to

think of the boxes as 8-bit bytes. One bit (a binary digit) is just a 0 or a

1, and a byte is made up of 8 bits, for example 11001011. These are just

base-2 numerals, so 5 in

decimal is 101, and although they are difficult for humans to read (unless

you’re used to them), computers live and breathe binary digits.

This is why the integer types all have numbers associated with them—the number

represents the number of bytes used to store the integer. So i64 requires 64

bits, while an i8 only requires 8. The reason for having different sizes is

that larger sizes take up more room (more bytes) in memory, but can also store

larger values (n bits can store 2n different numbers). All the other

types have sizes, too: a float is 32 bits for instance, and the number of bits

required to represent an aggregate type like a tuple or an array is (at least)

the sum of the sizes of their components.

So, reconsidering our very first example, where we stored an i64 value of 4

to represent how many cats we had, a more accurate diagram of the actual memory

layout in this situation is:

See how each i64 value takes up 8 bytes? Also, each byte has a memory

addresses, so the start of each i64 in memory is actually 8 bytes along from

the previous one.

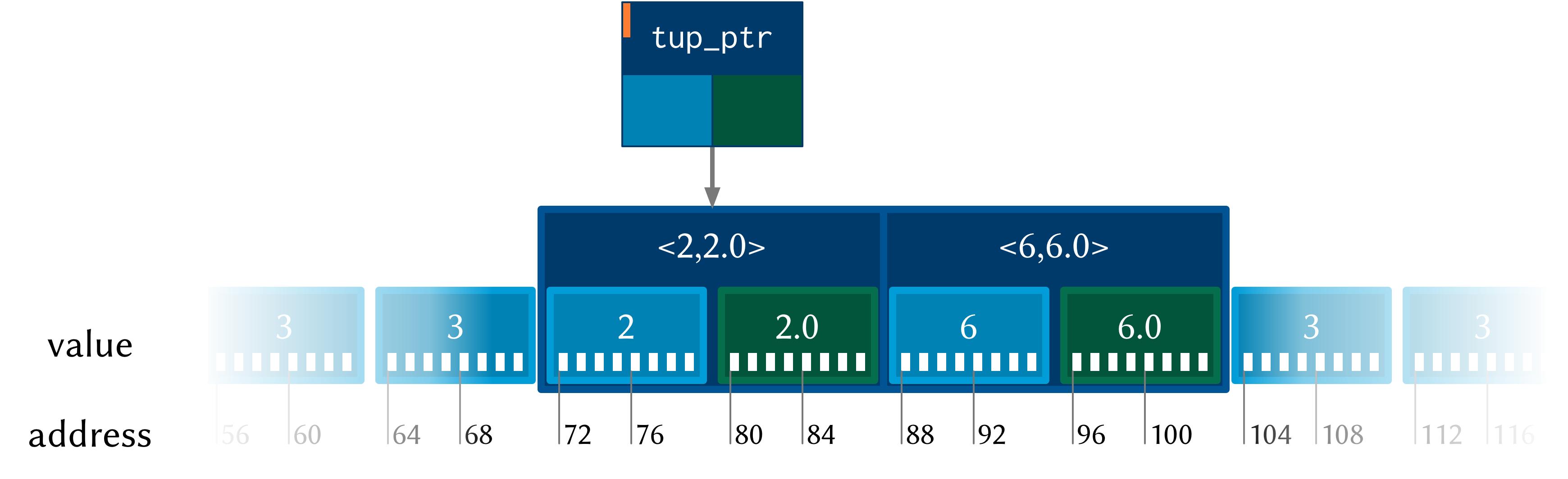

Now, consider the layout of an aggregate type like a tuple:

Each tuple contains (and therefore takes up the space of) an i64 and a

double. So the actual memory address offset between the beginning of

consecutive tuples is 16 bytes. But pref still works the same as in the i64*

case. (pref tup_ptr 1) gets the second tuple—it doesn’t try and read a tuple

from ‘half way in’.

This is one reason why pointers have types: the type of the pointer tells pref

how far to jump to get between consecutive elements (this value is called the

stride). This becomes increasingly helpful when working with pointers to

compound types: no-one wants figure out (and keep track of) the size of a tuple

like <i32,i8,|17,double|*,double> and calculate the stride manually.

Other benefits of using pointers

There are a few other situations where being able to pass pointers around is really handy.

- When the chunks of memory we’re dealing with are large, copying them around in memory becomes expensive (in the ‘time taken’ sense). So, if lots of different functions need to work on the same data, instead of copying it around so that each function has its own copy of the data, they can just pass around pointers to the same chunk of data. This means that each function needs to be a good citizen and not stuff up things for the others, but if you’re careful this can be a huge performance benefit.

- You can programatically determine the amount of memory to allocate, which is something you can’t to with xtlang’s array types.