Note-level music

This guide covers the basics of how to play instruments at a “note-level” (e.g.

play the G above middle C for 2 beats) in Extempore. If you’re satisfied with

just playing Extempore’s built-in instruments (which can be found in

libs/core/instruments.xtm) then you can just start at this guide. Finally,

this guide complements the pattern language one (an alternate way of triggering notes,

loops & patterns) and you can mix and match both approaches.

Setting up an instrument

This is about the simplest program you can write in Extempore. It loads an instrument and plays a single note.

;; load the instruments file

(sys:load "libs/core/instruments.xtm")

;; define a synth using the provided component fmsynth

(make-instrument synth fmsynth)

;; add the instrument to the DSP output sink closure

(bind-func dsp:DSP

(lambda (in time chan dat)

(synth in time chan dat)))

(dsp:set! dsp)

;; play a note on our synth

(play-note (now) synth (random 60 80) 80 (* 1.0 *second*))

To run this simple program copy the code into your editor and evaluate

it—either one line at a time or all at once. When you eval the final line (the

call to play-note) you should hear a single note play for one second. You can

re-evaluate that line as many times as you like—you should hear a sound each

time. Notice that random chooses a different pitch each time you evaluate.

Notice that Extempore is responsive, in fact you should be able to evaluate

play-note in time with a song playing on the radio. Extempore is a ‘live

performance instrument’ so it is designed to be responsive. This is what I mean

by interactive—we can evaluate code and view/hear results straight away.

We can also create Scheme functions to trigger more complex musical structures.

Evaluate the following expression to define a function chord that, when

called, will play a chord on the synth instrument.

(define chord

(lambda ()

(play-note (now) synth 60 80 *second*)

(play-note (now) synth 64 80 *second*)

(play-note (now) synth 67 80 *second*)))

Once chord is defined you can then call it as many times as you like by

evaluating the following expression:

(chord)

Congratulations, you have successfully written a Scheme function to play a C major chord. Try changing the pitch arguments to make different chords.

Playing in time

In keeping with traditions laid down in ages past by folks much smarter than me, I should also provide a “Hello World” example. Because we’re in Extempore, though, let’s add a bit of a twist: we’ll listen to the string “Hello World” instead of printing it to the log.

Following on from the code we evaluated before to set up the synth

; hello world as a list of note pitches

; transposed down two octaves (24 semitones)

(define melody (map (lambda (c)

(- (char->integer c) 24))

(string->list "Hello World!")))

; Define a recursive function to cycle through the pitches in melody

(define loop

(lambda (time pitch-list)

(cond ((null? pitch-list) (println 'done))

(else (play-note time synth (car pitch-list) 80 10000)

(loop (+ time (* *second* 0.5))

(cdr pitch-list))))))

; start playing melody

(loop (now) melody)

Note that loop is a recursive function—it calls itself. If you look

carefully at the code for loop you’ll see that it takes a list of pitches,

schedules the playing of the first pitch, then calls itself back with the

remaining pitches (if there are any). When we call loop in the last line with

time and pitch-list arguments, we should hear a sequence of pitches—and it

turns out that “Hello World” doesn’t make such a good musical example :)

Try evaluating the final (loop (now) melody) expression repeatedly—don’t

wait until the sequence has finished playing before you trigger another one.

Pretty cool, huh. Extempore is dynamic and interactive and was developed for use

in live performance.

Because coding in Extempore is so dynamic, if you re-evaluate a whole buffer you

may not get the results you expect! In particular, remember that if you have

multiple Extempore (*.xtm) file buffers connected to the same extempore

process then any evaluations you make will all go to the same place. For

example, there is only one dsp audio sink, so if you try to evaluate two

examples with different audio chain configurations you will almost certainly not

get what you expect. If in doubt, a good idea (particularly when getting

started) is to restart Extempore each time you want to run a new example or

start a new project.

We can use these ideas to make more complex musical patterns, with harmony, melody and rhythm as creative dimensions to explore.

It may seem a little strange when you first come to Extempore that there are no

‘musical’ functions provided for you—this is a conscious decision. While it is

impossible to provide a tool that does not in some way influence its user, my

goal with the pc_ivl.xtm Scheme library provide a musical framework that’s as

‘unopinionated’ as possible. Of course this is a somewhat ridiculous statement

given that straight out of the gate Extempore’s use of MIDI note numbers for

pitches strongly preferences a traditional diatonic tonal system. Having said

that, as shown in other guides, you can generate tones of any

frequency—quarter tone composers should not despair!

So with these thoughts in mind I want to stress that this guide shows some

ways of representing musical processes & data; not the way. For example, MIDI

pitch numbers are certainly not the only way to represent or control pitch in

Extempore—you are just as free to call the xtlang function _play_note (which

takes a frequency argument in Hz) instead of the Scheme wrapper play-note. As

I constantly harp on about, it’s xtlang turtles all the way down with all the

DSP code I use in this guide, so if you want to hack them to suit your needs you

can—even in the middle of a performance. Still, the musical frameworks exist

so that you don’t have to do the low level DSP stuff if you don’t want to, all

you have to think about is writing useful musical processes & representations!

I should also note that most of the music libraries are written in Scheme

(rather than xtlang), and in fact most of the code in this guide is also in

Scheme. xtlang does have its own version of callback, so you can also write

temporal recursions in xtlang, but in this guide I’ve chosen to use Scheme for

most of the high-level ‘control’ code (all the DSP code being called is still in

xtlang).

So enough with the lecture already! Let’s start by playing a sequence of notes.

Before we do that (if you haven’t already), you’ll have to set up an instrument

(in this case the built-in synth) and put it somewhere in the dsp output

callback:

(sys:load "libs/core/instruments.xtm")

;; define a synth using the provided component fmsynth

(make-instrument synth fmsynth)

;; add the instrument to the DSP output sink closure

(bind-func dsp:DSP

(lambda (in time chan dat)

(synth in time chan dat)))

(dsp:set! dsp)

Playing scales and chords

First, let’s implement a simple iterative process. Remember that in MIDI note

numbers (which play-note uses) 60 is middle C, 61 is C#, 62 is D,

etc…

(dotimes (i 8)

(play-note (+ (now) (* i 5000)) synth (+ 60 i) 80 4000))

That seems simple enough. But there is a problem here—we don’t have any

control over the iterator variable i in the dotimes loop. What if we want to

play a whole tone scale. Let’s use recursion to solve this problem. Ok Scheme

newbies, time find out about

named let!

;; recursive whole-tone scale

(let loop ((i 0))

(play-note (+ (now) (* i 2500)) synth (+ 60 i) 80 4000)

(if (< i 9) (loop (+ i 2))))

I’m sure there are a few people whispering he could have done that

with dotimes, but this is Scheme, so the quicker we move onto

recursion the better :)

So, linear sequences don’t seem to present a problem. How about a major scale? Recursion can handle this for us

;; recursive major scale

(let loop ((scale '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11 12))

(time 0))

(play-note (+ (now) time) synth (+ 60 (car scale)) 80 4000)

(if (not (null? (cdr scale)))

(loop (cdr scale) (+ time 5000))))

We also added a second argument to loop: time. Let’s use the time argument

to add changing durations to our scale.

;; recursive major scale with rhythm

(let loop ((scale '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11 12))

(dur '(22050 11025 11025 22050 11025 11025 44100 44100))

(time 0))

(play-note (+ (now) time) synth (+ 60 (car scale)) 80 (car dur))

(if (not (null? (cdr scale)))

(loop (cdr scale) (cdr dur) (+ time (car dur)))))

Now that we have pitches and rhythms mastered how do we go about playing a

chord? The new time argument from the previous examples should give you a

pretty good clue—we just ditch the time argument!

;; recursive chord

(let loop ((chord '(0 4 7)))

(play-note (now) synth (+ 60 (car chord)) 80 44100)

(if (not (null? (cdr chord)))

(loop (cdr chord))))

;; we could also write this

(let loop ((scale '(0 4 7)))

(cond ((null? scale) 'finished)

(else (play-note (now) synth (+ 60 (car scale)) 80 44100)

(loop (cdr scale)))))

C Major—nice! We seem to be using lists a lot, so you’re probably just dying

to use map, so here goes.

;; map calls lambda for each argument of list

(map (lambda (p)

(play-note (now) synth p 80 44100))

(list 60 63 67))

C minor that time, that’s cool. That way is much more concise, why don’t we

always use map? There are a couple of reasons why sometimes it’s better not to

use map but we’ll come to those soon enough. For the moment let’s look at how

we can use map to play a broken chord.

;; map broken chord

(map (lambda (p d)

(play-note (+ (now) d) synth p 80 (- 88200 d)))

(list 60 64 67)

(list 0 22050 44100))

One small thing to keep in mind: map is designed to return a new list of

values. The process of creating this list makes map slightly less efficient

than the function for-each, which is not specified to return a list but is

instead designed specifically to trigger side effects (i.e. playing notes in

this instance). So if you don’t need to return a list, use for-each instead of

map.

;; for-each broken chord with volumes

(for-each (lambda (p d v)

(play-note (+ (now) d) synth p v (- 88200 d)))

(list 60 64 67)

(list 0 22050 44100)

(list 90 50 20))

Ok, now we’ve covered the basics. Before we move on, if you haven’t read the time documentation it’s probably a good idea to go and read it now.

Temporal recursion

Once you’ve read the time

docs, you’ll be all set to start using callback. We’ve already looked at

various ways to play a sequence of notes, and we’re now going to expand on that

theme. Let’s define a function that uses callback to temporally recurse

through a list of pitch values.

;; plays a sequence of pitches

(define play-seq

(lambda (time plst)

(play-note time synth (car plst) 80 11025)

(if (not (null? (cdr plst)))

(callback (+ time 10000) 'play-seq (+ time 11025) (cdr plst)))))

(play-seq (now) '(60 62 63 65 67 68 71 72))

This should look very similar to the example in the previous section, but there

are some subtle differences. To demonstrate, let’s change play-seq so that it

keeps playing the sequence indefinitely.

;; loop over a sequence of pitches indefinitely

(define play-seq

(lambda (time plst)

(play-note time synth (car plst) 80 11025)

(if (null? (cdr plst))

(callback (+ time 10000) 'play-seq (+ time 11025) '(60 62 65))

(callback (+ time 10000) 'play-seq (+ time 11025) (cdr plst)))))

(play-seq (now) '(60 62 65))

Ok, now while play-seq is running, change the (60 62 65) (in the body of the

play-seq function) to (60 62 67) and re-evaluate the play-seq function.

Now try changing it to (60 62 67 69) and re-evaluating. Because play-seq

uses this list to reinitialize plst whenever plst is null, any changes we

make are reflected when this re-initialization occurs—a useful little trick.

Stop the play-seq function by re-defining play-seq to be the function that does

nothing: (define play-seq (lambda args)).

Let’s extend play-seq to include a rhythm list (rlst) as well.

;; plays a sequence of pitches

(define play-seq

(lambda (time plst rlst)

(play-note time synth (car plst) 80 (car rlst))

(callback (+ time (* .5 (car rlst))) 'play-seq (+ time (car rlst))

(if (null? (cdr plst))

'(60 62 65 69 67)

(cdr plst))

(if (null? (cdr rlst))

'(11025 11025 22050 11025)

(cdr rlst)))))

(play-seq (now) '(60 62 65 69 67) '(11025 11025 22050 11025))

Note that our pitch list and our rhythm list are different lengths. Unlike

for-each (and map) we can iterate through these two lists independently,

so they can be of different lengths. This allows us to play with various phasing

techniques. Have a play, change the lengths/values of both lists inside the

play-seq function, and remember to re-evaluate play-seq when you are ready

for your changes to take effect. Try calling play-seq again to start a second

sequence playing. Try to create a nice offset—you’ll need to evaluate the code

at just the right time :) Note that after the first iteration through the

sequence, both running instances of play-seq will assume the same lists

(because callback sets the same list values when it’s time to reinitialize the

lists). As an exercise for the reader, think about how you could avoid that

problem (i.e. keep the lists independent for each instance of play-seq).

Ok, so we can now manually change the lists that play-seq cycles through,

but what if we would like to change the list programmatically. No problem, just

use a function instead of a literal list—of course this is now no longer an

ostinati!

;; plays a random pentatonic sequence of notes

(define play-seq

(lambda (time plst rlst)

(play-note time synth (car plst) 80 (* .65 (car rlst)))

(callback (+ time (* .5 (car rlst))) 'play-seq (+ time (car rlst))

(if (null? (cdr plst))

(make-list-with-proc 4 (lambda (i) (random '(60 62 64 67 69))))

(cdr plst))

(if (null? (cdr rlst))

(make-list 4 11025)

(cdr rlst)))))

(play-seq (now) '(60 62 64 67) '(11025))

One final performance tip before we move on—musical performance of course! It’s really easy to add some metric interest by oscillating the volume to peak on down beats. We can make a small modification to the previous example to demonstrate this simple little cheat. Also we’ll shorten the durations a little (constant legato gets a touch boring).

;; plays a random pentatonic sequence of notes with a metric pulse

(define play-seq

(lambda (time plst rlst)

(play-note time synth (car plst)

(+ 60 (* 50 (cos (* 0.03125 3.141592 time))))

(* .65 (car rlst)))

(callback (+ time (* .5 (car rlst))) 'play-seq (+ time (car rlst))

(if (null? (cdr plst))

(make-list-with-proc 4 (lambda (i) (random '(60 62 64 67 69))))

(cdr plst))

(if (null? (cdr rlst))

(make-list 4 11025)

(cdr rlst)))))

(play-seq (now) '(60 62 64 67) '(11025))

Pitch classes

If you’ve read many 20th Century composition texts on pitch classes, you could be forgiven for thinking pitch class sets a rather dry subject and of limited compositional value. Oh, how wrong you would be! Pitch classes are actually not too tricky to understand and fantastically useful for the music programmer.

For those unfamiliar with pitch classes, they are based around the 12 semitones

of the chromatic scale, and each semitone is given it’s own class: C, C#, D,

D#/Eb, F, F# etc. Pitch classes also remove all octave reference and

enharmonic signature, because pitch

classes display enharmonic and octave equivalence (i.e. D#/Eb are the same

pitch class in any octave). Of course in a programming space we use numbers to

represent pitches, because numbers are easier for us to work with. So, instead

of B#/C/Db for example we use 0, C#/Db is 1, D is 2… through to

A#/B/Cb at 11 which rounds out the complete set of available pitch classes

0 to 11.

Now, the observant reader will note that we can use modulo arithmetic to find

MIDI pitches of octave equivalence by using mod 12. Try running this example,

and check the log for the printed results.

(dotimes (i 12)

(println 'modulo (+ i 60) 12 '=> (modulo (+ i 60) 12)))

Now, as previously discussed, Extempore does not include (by default) much

high-level musical support. However, there is pitch class (Scheme) library in

libs/core/pc_ivl.xtm. I encourage you to take a look at the pc_ivl.xtm file

and extend and replace things as you see fit—you’ll probably have your own

preferred way of working with pitch classes.

Let’s start with something simple. We can define a pitch class set by creating a

list of pitch classes that belong to the set. We can then test a pitch against

that set by using pc:?

(sys:load "libs/core/pc_ivl.xtm")

;; four examples tested against the pitch class set representation of a C major chord

(pc:? 60 '(0 4 7))

(pc:? 84 '(0 4 7))

(pc:? 35 '(0 4 7))

(pc:? 79 '(0 4 7))

We can also choose a random pitch from a pitch class set between a lower and upper bound.

;; this chooses a C in any octave

(pc:random 0 127 '(0))

;; this chooses any note from a D minor chord in octave 4

(pc:random 60 73 '(2 5 9))

;; this chooses any note from a C pentatonic octaves 3-6

(pc:random 48 97 '(0 2 4 7 9))

Let’s write a little organum piece. We’re going to write a strict parallel organum where we take a melody part and then transpose up a perfect forth or fifth (you can try both) to supply a harmony. What does this have to do with pitch classes? Well, you can’t just transpose up a fifth by adding 7 to everything:

;; up 7 semitones or a perfect fifth

(map (lambda (p)

(pc:? (+ p 7) '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11)))

(list 60 62 64 65 67 69 71))

;; up 5 semitones or a perfect forth

(map (lambda (p)

(pc:? (+ p 5) '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11)))

(list 60 62 64 65 67 69 71))

;; up 4 semitones or a major third

(map (lambda (p)

(pc:? (+ p 4) '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11)))

(list 60 62 64 65 67 69 71))

Based on a C-major key pitch class set, B up 7 semitones (a perfect 5th) gives

us F#. F up by 5 semitones (a perfect 4th) gives Bb and if we have the

audacity to try 4 semitones (a major 3rd)—well basically nothing works. Notice

that we do use map here instead of for-each because we do want to return a

list (of boolean values). So the answer is to use pc:relative, which will

choose a pitch value from the pitch class relative to our current pitch.

;; this gives us 62

(pc:relative 60 1 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

;; this gives us 67

(pc:relative 60 4 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

;; this gives us 67 as well

(pc:relative 67 0 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

;; this gives us 57 (yes you can go backwards)

(pc:relative 60 -2 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

One more rule about an organum: we need our melody and harmony to start and finish on the same note (C). Here’s one way we could go about the task:

;; define a melody

(define melody (make-list-with-proc 24

(lambda (i)

(pc:random 60 73 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11)))))

;; define harmony up a perfect 5th (4 places away in the pitch class set)

(define harmony (map (lambda (p)

(pc:relative p 4 '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11)))

melody))

;; set c at start and end

(set! melody (cons 60 melody))

(set! harmony (cons 60 harmony))

(set! melody (reverse (cons 60 (reverse melody))))

(set! harmony (reverse (cons 60 (reverse harmony))))

;; random rhythm

(define rhythm (make-list-with-proc 24 (lambda (i) (random '(44100 22050)))))

;; set long start and end to rhythm

(set! rhythm (cons 88200 rhythm))

(set! rhythm (reverse (cons 88200 (reverse rhythm))))

(define organum

(lambda (time mlst hlst rlst)

(play-note time synth (car mlst) 60 (car rlst))

(play-note time synth (car hlst) 60 (car rlst))

(if (not (null? (cdr mlst)))

(callback (+ time (* .5 (car rlst))) 'organum (+ time (car rlst))

(cdr mlst)

(cdr hlst)

(cdr rlst)))))

;; start

(organum (now) melody harmony rhythm)

It was a little out of character for the melody to leap around so much, so let’s

also use pc:relative to implement a random walk melody. The rest of the code

can stay the same, but remember to reevaluate everything that the change

effects—in this case everything to do with creating melody and harmony.

;; define a random walk melody seeded with 60

;; (we remove this at the end with cdr)

(define melody

(let loop ((i 0)

(lst '(60)))

(if (< i 24)

(loop (+ i 1)

(cons (pc:relative (car lst)

(random '(-1 1))

'(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

lst))

(cdr (reverse lst)))))

Of course we could easily use larger leaps by changing (random '(-1 1)) to

(random '(-2 -1 1 2 3)) for example. pc:relative can be a useful way of

constraining (and then later releasing) melodic invention.

Making chords with pitch classes

Ok, that’s enough 13thC noise, let’s go hardcore 20thC and make a I IV V

progression :) But first a crazy 21stC chord. Once crazy-chord is running,

slowly start removing pitch classes from the end of the set. And just a heads

up—I’m not going to remind you to re-evaluate anymore :) Listen to the C-major

chord that starts to evolve. If your machine will handle a higher callback rate

then go for it, we’re after a wash of sound here. Try choosing a sound with a

delay for extra impact.

(define crazy-chord

(lambda (time)

(play-note time synth (pc:random 24 97 '(0 4 7 10 2 3 5 9 6 11 1)) 80 500)

(callback (+ time 1000) 'crazy-chord (+ time 2000))))

(crazy-chord (now))

Ok, so we’ve seen how we can use a pitch class to represent a chord.

pc_ivl.xtm also includes a useful little function pc:make-chord for

returning a ‘random’ chord based on a pitch class set. Let’s take a look at this

in action:

;; C-major and repeat

(define chords

(lambda (time)

(for-each (lambda (p)

(play-note time synth p 80 10000))

(pc:make-chord 60 72 3 '(0 4 7)))

(callback (+ time 10000) 'chords (+ time 11025))))

(chords (now))

Hey, our friend for-each is back. Now while chords is playing, start

expanding the range (i.e. drop the 60 down and raise the 72 up).

pc:make-chord returns as many notes as we request in the 3rd (number)

argument, which is 3 in the example above. It tries to evenly distribute the

notes of the chord across the specified range. It also attempts to use each

class in the pitch class set. However, it does not make any guarantees about

what order to choose classes from the pitch class set. You might also like to

change the number of notes being generated for our chord—try changing 3 to

1, or 2, 4, 5…

I’m getting a little sick of C-major, so let’s add chord IV (F major) and V

(G major) to the progression and make a random chord change one in five

callbacks. Note that random can just as easily choose a list from a list as

an atom from a list.

;; I IV V

(define chords

(lambda (time chord)

(for-each (lambda (p)

(play-note time synth p 80 10000))

(pc:make-chord 48 90 3 chord))

(callback (+ time 10000) 'chords (+ time 11025)

(if (> (random) .8)

(random '((0 4 7) (5 9 0) (7 11 2)))

chord))))

(chords (now) '(0 4 7))

There’s a lot more we can do with pitch classes. You can go and explore right now if you like, and there’s also plenty more to come in this guide too.

Harmony

Time to move onto some serious composition, and what could be more serious than diatonic harmony :)

Now everyone knows that you don’t follow V with ii, at least this is

probably what your music teacher tried to tell you :) 18thC Harmony lessons

aside, it is worth questioning the validity of making random chord changes a

progression.

A Russian mathematician named Andrey Markov came up with one neat solution which we’re going to pinch (he was actually interested in russian language usage, but hey whatever). His work stated that you can construct a probability matrix that outlines the probability of any new state occurring based on a current state.

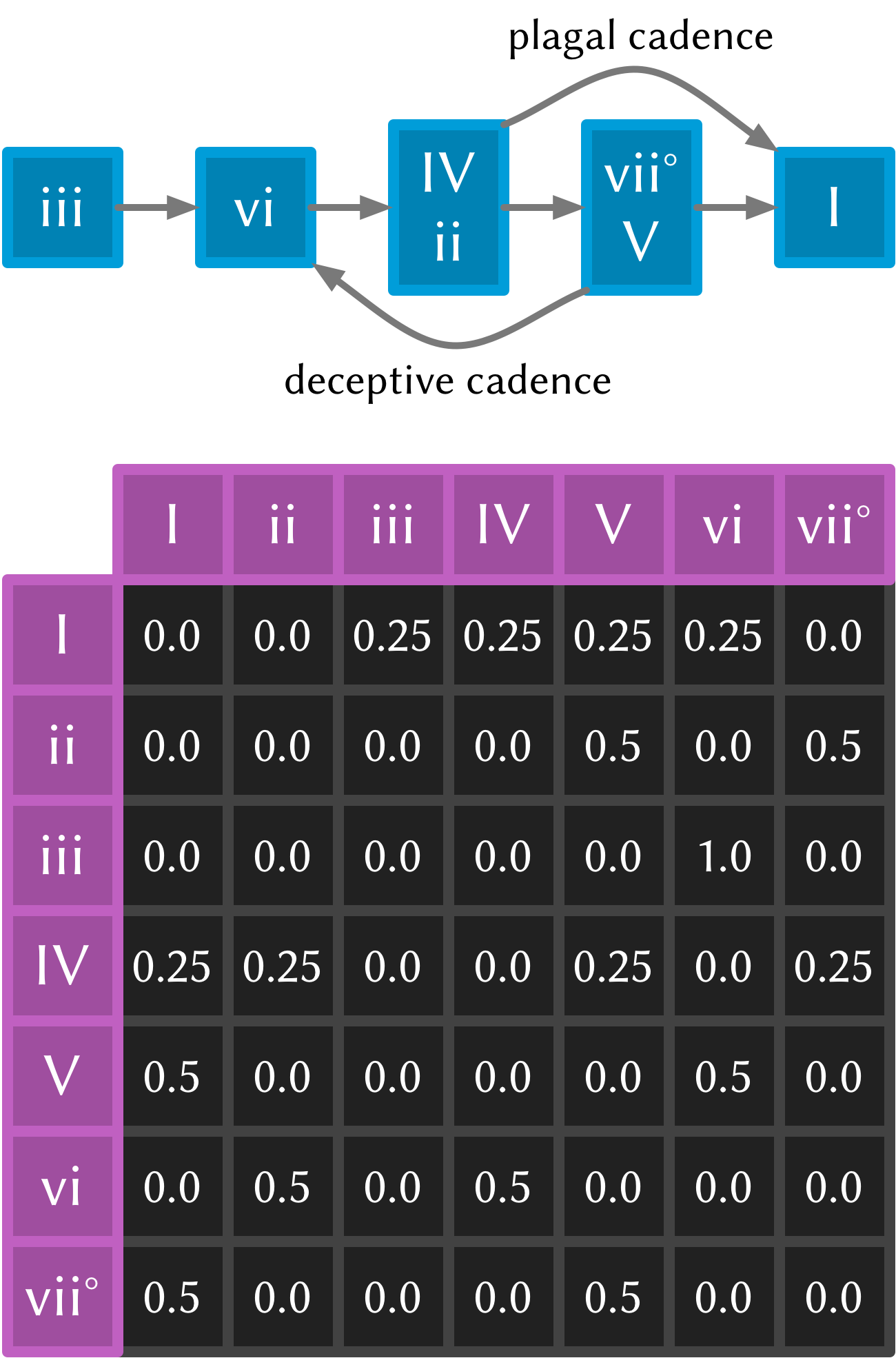

So let’s look at a very traditional picture (for simplicity’s sake) of Western

Diatonic Harmony. Remembering that in the major key our scale degrees give us

the following chords: I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, and viio. Roman

uppercase letters are major chords, roman lowercase are minor chords, and viio

is a diminished chord. When we add the circle of 5ths into the mix, we end up

with a chord progression chart that in it’s simplest form looks something like

this (I’ve taken a few liberties based on a few hundred years of usage).

So reading this diagram from left to right we can move from iii to vi. Then

from vi to either IV or ii. From IV we can then move to either viio,

ii, V or I. From ii we can move to either viio or V. From viio we

can move to V or I. From V we can move to either vi or I. And from I

we can move anywhere—however in the matrix above I have limited I’s movement

to iii IV V and vi. This is a pretty limited view of the harmonic world,

but we’ll stick with it for today.

Now for the cool part: we can use random and assoc to trivially implement

this markov matrix in Extempore (if you don’t know what assoc does then

Dybvig’s The Scheme Programming

Language is a good online resource).

For this first effort we’re going to assume the key of C major and I’m going to

limit the example to the I, IV and V chords only.

;; markov chord progression I IV V

(define progression

(lambda (time chord)

(for-each (lambda (p)

(play-note time synth p 80 40000))

(pc:make-chord 60 73 3 chord))

(callback (+ time 40000) 'progression (+ time 44100)

(random (cdr (assoc chord '(((0 4 7) (5 9 0) (7 11 2))

((5 9 0) (7 11 2) (0 4 7))

((7 11 2) (0 4 7)))))))))

(progression (now) '(0 4 7))

Now that was pretty easy, but our list of chords is a little unwieldy.

Fortunately pc_ivl.xtm has a function that will help us out with that problem.

pc:diatonic is designed to return a chord’s pitch class given a key and a

scale degree. So if we use (pc:diatonic 0 '^ 'iii) we are asking for iii in

the key of C (0) major (^). ^ is major and - is minor (note also that we

have to quote the symbols as we pass them to pc:diatonic). Also, because

Scheme symbols are lowercase only we use i for I v for V, etc. Because

pc:diatonic is passed major or minor it is clever enough to know that i

means I and that vii means viio in the major key. In minor i will be

minor etc… Let’s look at an example that implements our entire matrix.

;; markov chord progression I ii iii IV V vi vii

(define progression

(lambda (time degree)

(for-each (lambda (p)

(play-note time synth p 80 40000))

(pc:make-chord 48 77 5 (pc:diatonic 0 '^ degree)))

(callback (+ time 40000) 'progression (+ time 44100)

(random (cdr (assoc degree '((i iv v iii vi)

(ii v vii)

(iii vi)

(iv v ii vii i)

(v i vi)

(vii v i)

(vi ii))))))))

(progression (now) 'i)

Now I’m getting tired of the synth we’ve been playing all along—let’s try

playing this on an organ instead. Let’s also make a couple of performance

changes:

- we’ll randomly add mordants

- we’ll make I and IV twice the duration of the other chords

;; create our organ instrument (again, analogue

;; is defined in libs/core/instruments.xtm

(make-instrument organ analogue)

;; add the instrument to the DSP output sink closure

(bind-func dsp:DSP

(lambda (in time chan dat)

(+ (synth in time chan dat)

(organ in time chan dat))))

;; mordant

(define play-note-mord

(lambda (time inst pitch vol duration pc)

(play-note (- time 5000) inst pitch (- vol 10) 2500)

(play-note (- time 2500) inst (pc:relative pitch 1 pc) (- vol 10) 2500)

(play-note time inst pitch vol (- duration 5000))))

;; markov chord progression I ii iii IV V vi vii

(define progression

(lambda (time degree)

(let ((dur (if (member degree '(i iv)) 88200 44100)))

(for-each (lambda (p)

(if (and (> p 70) (> (random) .7))

(play-note-mord time synth p

(random 70 80)

(* .9 dur) '(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

(play-note time organ p (random 70 80) (* .9 dur))))

(pc:make-chord 40 78 4 (pc:diatonic 0 '^ degree)))

(callback (+ time (* .9 dur)) 'progression (+ time dur)

(random (cdr (assoc degree '((i iv v iii vi)

(ii v vii)

(iii vi)

(iv v ii vii i)

(v i vi)

(vii v i)

(vi ii)))))))))

(progression (now) 'i)

If you had any temporal recursion-based music (e.g. the previous progression

callback loop) playing when you evaluated the define-instrument form, then

you may have heard a pause in the audio output while the xtlang code compiled.

This is because the compilation of organ was happening in the same Scheme

process as the progression callback loop. The Scheme process has to wait until

the compiler is done before it can continue with other Scheme code execution.

The solution to this problem is to run the progression callback in a separate

process. There’s a blog guide in the works about how Extempore handles multiple

processes and concurrency, but for the moment if you’re interested have a look

at the stuff at the bottom of the examples/contrib/horde3d_knight.xtm example

file. The ipc:-prefixed functions create and manage multiple processes in

Extempore. If you’re just mucking around at home, it’s probably not a big

problem to have a small pause in the audio output when you re-compile things.

But if it is a problem, take heart that there are fairly straightforward ways

to get around the problem.

Ok so, as a final exercise let’s try to make a simple organ ditty for 5 parts,

and we should try to have some simple part movement (i.e. not just block chords

everywhere). Now to do this, we’re going to cheat and use pc:relative to move

from our chord tones on off beats—Schoenberg would be most displeased! We’ll

also add an even longer duration option for I and IV.

;; Quintet

(define progression

(lambda (time degree)

(let ((dur (if (member degree '(i iv)) (random (list 88200 (* 2 88200))) 44100)))

(for-each (lambda (p)

(cond ((and (> (random) .7) (< dur 80000))

(play-note time organ p (random 60 70) (* .3 dur))

(play-note (+ time (* .5 dur))

organ

(pc:relative p (random '(-1 1))

'(0 2 4 5 7 9 11))

(random 60 80)

(* .3 dur)))

(else (play-note time

organ

p

(random 60 70)

(* .7 dur)))))

(pc:make-chord 36 90 5 (pc:diatonic 0 '^ degree)))

(callback (+ time (* .8 dur)) 'progression (+ time dur)

(random (cdr (assoc degree '((i iv v iii vi)

(ii v vii)

(iii vi)

(iv v ii vii i)

(v i vi)

(vii v i)

(vi ii)))))))))

(progression (now) 'i)

Beat & tempo

“Bring back the beat” I hear you say. OK, on to beat & tempo. In this section we’re going to need a drum instrument.

To set up a drumkit you can either follow the sampler guide which shows you how can set up your own sampler

instrument (and guides you through making a drum sampler). Or you could just

load (sys:load "examples/sharedsystem/setup.xtm") and it’ll be done for you.

Got a drum sampler set up? Great. So far we have been using Extempore’s default

time standard—samples per second—to control rhythm and duration information.

As musicians though, we are more used to working with beats and tempo. Here’s a

simple example working with samples. At the end of this page you’ll find a list

of general MIDI drum numbers which I’ll be using in this tutorial:

*gm-cowbell*, etc…

;; assuming you've set up and loaded the drums sampler

(bind-func dsp:DSP

(lambda (in time chan dat)

(+ (synth in time chan dat)

(organ in time chan dat)

(drums in time chan dat))))

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time dur)

(play-note time drums *gm-cowbell* 80 dur)

(callback (+ time (* .5 dur)) 'drum-loop (+ time dur) (random '(22050 11025)))))

(drum-loop (now) 11025)

And here’s one way that we could go about transforming this into a more abstract notion of time.

;; beat loop

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time dur)

(let ((d (* dur *samplerate*)))

(play-note time drums *gm-cowbell* 80 d)

(callback (+ time (* .5 d)) 'drum-loop (+ time d) (random '(0.5 0.25))))))

(drum-loop (now) 0.25)

So what’s the advantage here—is it more work for no benefit? Well, there are actually two big advantages:

- Ratios are easier to deal with than samples:

0.25is easier to remember than11025(assuming a samplerate of44100) - this system supports alternate tempos, so we can change tempo without having to change any rhythm values.

Let’s play back the same example at 120 beats per minute (bpm)—remembering that by default the Extempore metronome runs at 60 bpm. We’ll also add triplets to our quavers and semi-quavers.

;; beat loop at 120bpm

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time dur)

(let ((d (* dur .5 *samplerate*)))

(play-note time drums *gm-cowbell* 80 d)

(callback (+ time (* .5 d)) 'drum-loop (+ time d)

(random (list (/ 1 3) 0.5 0.25))))))

(drum-loop (now) 0.25)

Let’s try using an oscillator to drift the playback speed back and forth over time.

;; beat loop with tempo shift

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time dur)

(let ((d (* dur (+ .5 (* .25 (cos (* 16 3.141592 time)))) *samplerate*)))

(play-note time drums *gm-cowbell* 80 d)

(callback (+ time (* .5 d)) 'drum-loop (+ time d)

(random (list 0.5))))))

(drum-loop (now) 0.5)

All values are now 0.5 so we should get a nice even rhythm with a tempo change

over time. But if you’re evaluating and listening to the results of drum-loop,

it’s obvious that it doesn’t sound very even! It turns out that tempo is a lot

more subtle than you might expect. What we actually need is a linear function

that can more evenly distribute our beats with respect to tempo changes.

As it turns out, runtime/scheme.xtm (which is loaded by default on startup)

includes a function called make-metro which will solve a few of these

problems. At it’s simplest, make-metro is a function that accepts a tempo and

returns a closure. We can then call that closure with a (cumulative) time in

beats and have an absolute sample number returned to us. So the metronome

provides a mapping from beats (which are nice to work with) to samples (which

Extempore needs to work with). This makes more sense as a practical exercise, so

let me demonstrate.

;; create a metronome starting at 120 bpm

(define *metro* (make-metro 120))

;; beat loop

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time duration)

(println time duration)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-cowbell* 80 (*metro* 'dur duration))

(callback (*metro* (+ time (* .5 duration))) 'drum-loop (+ time duration)

(random (list 0.5)))))

(drum-loop (*metro* 'get-beat) 0.5)

You should notice a couple of things:

- We start our loop by calling

(*metro* 'get-beat). This asks our*metro*closure to return the next available beat number to us, i.e.(fmod beat 1.0).*metro*starts ticking over beats as soon as it’s initialized timeis now in beats (not in samples) and is cumulative. Check your logview for an idea about what the value oftimeis each time through the drum-loop. Also remember that floating point is subject to rounding error—but don’t lose too much sleep over that for the moment(*metro* 'dur duration)returns a duration in samples relative to the current tempo- The closure returned by

(make-metro)is really a kind of object and the symbol names are method names—message names really. Any arguments after the message name are passed with the message and dispatched inside the closure to the appropriate ‘method’. What we are using here is a form of message passing. Who said Scheme wasn’t an OO language!

How about those tempo changes? No problem—we just need to use pass another

message to *metro* closure: set-tempo, which sets a new tempo in bpm (and

don’t forget to quote the symbol).

;; create a metronome starting at 120 bpm

(define *metro* (make-metro 120))

;; beat loop with tempo shift

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time duration)

(*metro* 'set-tempo (+ 120 (* 40 (cos (* .25 3.141592 time)))))

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-cowbell* 80 (*metro* 'dur duration))

(callback (*metro* (+ time (* .5 duration))) 'drum-loop (+ time duration)

(random (list 0.5)))))

(drum-loop (*metro* 'get-beat) 0.5)

More cowbell! Much better, I’m sure you will agree. Now the really cool thing

about *metro* is that you can now use it to sync as many callback loops as

you like. Let’s add a second drum-loop call. Notice also that we have added an

argument to the get-beat message that asks the metronome to return a beat

number which is equal to 0 mod 4. I’m going to play cowbell and triangle

with a slight 0.25 offset.

;; create a metronome starting at 120 bpm

(define *metro* (make-metro 120))

;; beat loop with tempo shift

(define drum-loop

(lambda (time duration pitch)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums pitch 80 (*metro* 'dur duration))

(callback (*metro* (+ time (* .5 duration))) 'drum-loop (+ time duration)

duration

pitch)))

;; shift tempo over time using oscillator

(define tempo-shift

(lambda (time)

(*metro* 'set-tempo (+ 120 (* 40 (cos (* .25 3.141592 time)))))

(callback (*metro* (+ time .2)) 'tempo-shift (+ time .25))))

(drum-loop (*metro* 'get-beat 4) 0.5 *gm-cowbell*)

(drum-loop (*metro* 'get-beat 4.25) 0.5 *gm-open-triangle*)

(tempo-shift (*metro* 'get-beat 1.0))

Ahhh, like clockwork. Notice that now we are running two independent drum-loop

temporal callbacks we need to put the tempo shift in a separate function—we

don’t want the tempo to be set independently by two seperate loops!

We now have almost enough information to build our first drum machine!

Extempore also has a very useful function called make-metre. Like the

make-metro function, the make-metre function returns a closure which can

subsequently be called. make-metre returns a closure that returns #t or #f

based on a simple query: given an accumulated beat, are we on a certain metric

pulse? A practical demo should make this a little clearer.

First though, a brief explanation of make-metre initial arguments. The first

argument is a list of numerators and the second argument is a single

denominator. What this implies is that make-metre can work with a series of

revolving metres. Some examples:

(make-metre '(4) 1.0)gives us4times1.0metric pulses (recurring every4/4bars);(make-metre '(3) 0.5)gives us3times0.5metric pulses (recurring every3/8bars)(make-metre '(2 3) 0.5)gives us2times0.5then3times0.5metric pulses (a recurring series of2/83/82/83/82/83/8…).

Let’s try using a make-metre. We’ll only play the first beat of each

bar.

(define *metro* (make-metro 90))

;; a 2/8 3/8 2/8 cycle

(define *metre* (make-metre '(2 3 2) 0.5))

;; play first beat of each 'bar'

(define metre-test

(lambda (time)

(if (*metre* time 1.0)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-side-stick* 80 10000))

(callback (*metro* (+ time 0.4)) 'metre-test (+ time 0.5))))

(metre-test (*metro* 'get-beat 1.0))

Well, that was easy. Let’s complicate things just a little by adding a second metre. We’ll play the side stick for the first metre and the snare for the second metre.

;; classic 2 against 3

(define *metro* (make-metro 180))

;; 3/8

(define *metre1* (make-metre '(3) .5))

;; 2/8

(define *metre2* (make-metre '(2) .5))

;; play first beat of each 'bar'

(define metre-test

(lambda (time)

(if (*metre1* time 1.0)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-side-stick* 80 10000))

(if (*metre2* time 1.0)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-snare* 60 10000))

(callback (*metro* (+ time 0.4)) 'metre-test (+ time 0.5))))

(metre-test (*metro* 'get-beat 1.0))

The French composer Olivier Messiaen is well known for (amongst other things)

symmetrical metric structures. Let’s follow his lead and build up a relatively

complex poly-symmetric drum pattern. Again, we’re going to work with two

competing metric structures—both of which will be symmetric (2/8 3/8 4/8 3/8

2/8) and (3/8 5/8 7/8 5/8 3/8). Because the second metric structure is uneven

in length we should get some nice phasing effects, a la Steve Reich. I’m also

going to add some hi-hats to give it a constant pulse.

;; messiaen drum kit

(define *metro* (make-metro 140))

(define *metre1* (make-metre '(2 3 4 3 2) .5))

(define *metre2* (make-metre '(3 5 7 5 3) .5))

;; play first beat of each 'bar'

(define metre-test

(lambda (time)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums

(random (cons .8 *gm-closed-hi-hat*) (cons .2 *gm-open-hi-hat*))

(+ 40 (* 20 (cos (* 2 3.141592 time))))

(random (cons .8 500) (cons .2 2000)))

(if (*metre1* time 1.0)

(begin (play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-snare* 80 100000)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-pedal-hi-hat* 80 100000)))

(if (*metre2* time 1.0)

(begin (play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-kick* 80 100000)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-ride-bell* 100 100000)))

(callback (*metro* (+ time 0.2)) 'metre-test (+ time 0.25))))

(metre-test (*metro* 'get-beat 1.0))

There are a couple of things to note in the previous example. Firstly, our old

oscillating volume is back in the hi-hat parts. We are also using a weighted

random for both the choice of hi-hat pitch and the length of the hi-hat sound.

Also notice that we are moving around our callback faster than before—but this

is fine as long as our time increment has a suitable ratio to both metres.

Putting it all together

Let’s keep going with this idea and add some pitched musical content as well,

using the synth and organ instruments we were using earlier

(sys:load "libs/core/pc_ivl.xtm")

;; messiaen drum kit

(define *metro* (make-metro 140))

(define *metre1* (make-metre '(2 3 4 3 2) .5))

(define *metre2* (make-metre '(3 5 7 5 3) .5))

;; play first beat of each 'bar'

(define metre-test

(lambda (time degree)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums

(random (cons .8 *gm-closed-hi-hat*) (cons .2 *gm-open-hi-hat*))

(+ 40 (* 20 (cos (* 2 3.141592 time))))

(random (cons .8 500) (cons 2 2000))

9)

(play-note (*metro* time) synth

(pc:random 90 107 (pc:diatonic 9 '- degree))

(+ 50 (* 25 (cos (* .125 3.141592 time))))

100)

(if (*metre1* time 1.0)

(begin (play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-snare* 80 10000)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-pedal-hi-hat* 80 100000)

(play-note (*metro* time) organ

(+ 60 (car (pc:diatonic 9 '- degree)))

60

10000)))

(if (*metre2* time 1.0)

(begin (play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-kick* 100 100000)

(play-note (*metro* time) drums *gm-ride-bell* 100 100000)

(for-each (lambda (p)

(play-note (*metro* time) synth p 70 10000))

(pc:make-chord 65 80 3 (pc:diatonic 9 '- degree)))))

(callback (*metro* (+ time 0.2)) 'metre-test (+ time 0.25)

(if (= 0.0 (modulo time 8.0))

(random (cdr (assoc degree '((i vii vii vi)

(n v)

(vi n)

(v vi i)

(vii i)))))

degree))))

(metre-test (*metro* 'get-beat 1.0) 'i)

In this example we have used many of the techniques picked up in previous tutorials, so take some time and have a good look through this code. If you can understand it, then you’re well on your way to making music in Extempore. It’s also a good starting point for changing things yourself—there are plenty of interesting parameters & code chunks to tweak. Get in there and try it, and don’t be afraid to break things :)

And remember, the note-level control that we’ve looked at in this tutorial is just one way to use Extempore. You can also do DSP, graphics, distributed computing, network IO, high-performance number-crunching, and many other things.